The road up from the coast

Where we’re going next

G Says…

Continuing on from our previous post…

We’re up bright and early, partly due to worrying about frostbite in this chilly little house we rented for the nightand decide jumping into a car with not only a heater but heated seats will be a good idea. The scruffy dog leaps out from the bushes as I get to where I parked the car, determined not to let us leave without saying a lengthy goodbye. He brings me a filthy and much chewed stick which is almost as unwholesome as himself and I throw it for him for a while. He’s a gorgeous dog and a real character. We will miss him and I tell him so. I glance at the rear view mirror as we leave and he is sitting on the car park looking absolutely bereft. I’m so relieved we’ve only stayed for one night; any longer and I’d have smuggled him into the back seat.

Marigold decides today she would like to choose our route solely on which place name takes her fancy, so that’s what we do. It’s not sensible, it’s not particularly practical, but we do it anyway, so be aware if you ever wished to recreate today’s odyssey, there are easier ways of getting from place to place.

Even so, ‘a good traveller has no fixed plans and is not intent on merely arriving,’ as Lao Tzu said. He also gave the world ‘a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step,’ and several other quotes that have become part of everyday language. Not bad for someone who died in 531 AD, so there’s hope yet for Marigold’s undoubted wisdom to be recognised, eventually.

Random directions are one of the chief joys of travel and today throws up some unexpected gems.

We set off up the very steep track, very relieved not to meet anyone coming the other way, and head for Atalbeitar, the nearest village. It turns out not be car friendly as there’s no access road and only donkey tracks leading into and throughout the village. We don’t see any donkeys, but don’t see any people here either.

We brave the morning chill and wander around a bit. There are no shops, no bars and seemingly no inhabitants but a couple of smoking chimneys suggest they are inside keeping warm, sensible folk.

Altabeitar is the smallest of the seven villages which make up the ancient Moorish district of La Tah in the high Alpujarras. Taha is the Moorish word for obedience and this whole region used to divided into separate groups or ‘Tahas,’ but this group of seven is the only one to retain the name.

Mostly untouched by tourism, life in this isolated area life goes on much as it always has, in an unhurried and peaceful manner.

We find out the village stands at 1,150 metres above sea level, hence the early morning chill, and, supposedly, has 31 permanent residents. There are more than 31 houses, so even if they have one each there won’t be a housing shortage and the church looks as if it could contain the population three times over.

We go to see whether the nearby village, Pitres, is any livelier. Well, it’s bigger, quite a lot bigger, but still not exactly lively. There’s an artisan chocolate company ‘ Chocolates Sierra Nevada – here so we’re quite excited, but not for long as it’s closed. As is everywhere else, apart from a tiny shop, a terraced cottage with one room turned into a ‘shop’ which contains absolutely nothing we want to buy. They do have such oddities as carrot jam and artichoke jam for sale though.

‘Who buys this stuff?’ I wonder.

Marigold shrugs her shoulders. The man standing in the doorway, presumably the owner, walks over and points at a display of firelighters which he’s taken the trouble to arrange in a pyramid shape. We smile in appreciation and finally find a small bag of biscuits to buy so his feelings won’t be hurt. Oh, the pressures of being a foreigner in another land, ever mindful we are representing our nation in the eyes of others.

Hint, that last sentence may contain sarcasm. Even though it’s true as well. Let’s call it a slight exaggeration then.

The biscuits were dreadful, of course. Soggy, probably went out of date in the last century and almost entirely tasteless. Yes, of course I ate them. Marigold is far too fussy sometimes. She mutters something that sounds like ‘war boy,’ a reference to the one time I mentioned spending my early years in the days when rationing was in force. Times were hard then, I said, only having one potato a week to eat and wearing my grandad’s old clogs. Not to mention wearing a gas mask every day to make sure it didn’t go to waste. It falls on deaf ears.

There’s a small cage with a few chickens in next to one of the houses, the shop in a front room and that’s about it for Pitres. The chickens do their best, but even their efforts to please can’t sustain us for long. There are bars here, two discos, several hostels and a hotel, but they’re all closed. Bet this place is a riot in summer. They may even get the chance to buy chocolate. Spring onion jam too.

When these chickens are the highlight of your village…

Pitres is somewhat a figure of fun locally as a politician once asked the residents what amenities they would like him to obtain on their behalf if he was elected. The villagers conferred and came up with the idea that Pitres could become a port so the men would have more work. The politician didn’t hesitate before agreeing to bring the sea up the mountain to Pitres and thus set up a port. There’s a boat and a big anchor to greet visitors to the village so at least they’re now able to laugh at their own expense.

The request for the village to be made into a port has another legacy: a fiesta where sardines are ‘planted’ in a dry riverbed and solemnly watered to make them grow. Side splitting stuff, I imagine for those lucky enough to be there at the time. Perhaps not.

We drive next to three of the nearest villages: Capileira, Bubion and Pampaneira, perched on the slopes of snow covered Mulhacen, the highest point in mainland Spain.

We start at the highest point, Capileira, and work our way down. Capileira is not the highest village we’ll reach today, it’s only the second highest in the region, but we notice the immediate drop in temperature. When we left the coast a couple of days ago the car showed 24 degrees as the outside shade temperature; up here it’s showing as 2 degrees and the ‘warning, frost alert’ symbol lights up even more brightly on the dashboard.

Even so, it’s sunny, there’s blue sky above and we wander around looking and feeling like (inadequately equipped) Polar explorers for at least ten minutes, admiring hand woven rugs we don’t need, artisan style rustic pottery that’s ludicrously expensive and of course hams.

The Alpujarras are famous for hams, hung outside in the frigid mountain air to dry naturally and add flavour. Alpujarras hams are highly prized, the Spanish love them, and we were offered samples wherever we went today. Far more samples than normal, this generosity must be prompted by the scarcity of tourists in the winter months. Marigold declines all the offers; I accept ‘ it’s a ‘Marmite Style situation,’ or as Marigold says, quite often, I’m just greedy.

We love the haphazard nature of these mountain villages, their narrow streets twisting and turning, whitewashed stone walls and pots of flowers everywhere – more geraniums than Kew Gardens. There’s a uniformity about the roofs, even a ‘new build’ house has a flat roof, but there aren’t many new houses, this place looks much the same as it did hundreds of years ago. Flat stones are laid over chestnut wood beams and the gaps are packed with clay and grey sand. As they do in the Moroccan mountains, these roofs appear to be a misguided design choice, but they endure throughout even the harshest climate. On top are tall chimney stacks, often several of them on the same roof and they offer a touch of individuality.

These houses were built with the living quarters above a ground floor level where the animals were housed, pigs, goats, chickens, perhaps a mule. That’s still the case in the High Atlas, but here we glimpsed only the odd motorbike or washing machine, not a pig to be seen. Such is progress.

Later on we’re driving merrily along, admiring the tenacity and optimism of farmers who cultivate vines to make wine at such high altitudes when we see one such farmer hard at work. He’s following a pair of horses, ploughing the land between rows of vines. This isn’t an immaculate Bordeaux vineyard, it’s a scruffy, stony field, on a steep slope a very long way above sea level and surely these ancient vines will struggle to produce enough grapes to justify his labour. We decide the low yield from these venerable stumps will produce either very bad wine or something very special. The oenophile in me hopes it’s the latter.

There are four official languages in Spain (Castilian, Catalan, Basque and Galician), plus several regional dialects such as Andalusian and Valencian. In England, natives of Liverpool, Gateshead and London speak the same language, but in full flow their accents make perfect understanding difficult for many of their fellow citizens. Spain is a big country and a Catalan or Basque speaker would be almost unintelligible to a Spanish person in Madrid.

When we bought our first finca our closest neighbour came over for a ‘chat.’ We spoke and understood a little Spanish, but couldn’t understand a word he said. A few days later a Spanish friend came to visit us. He’s a university lecturer in Barcelona, a throughly cultured and erudite man, like all our friends, (!!!) but his ‘Spanish’ proved sadly inadequate when he tried to speak with our neighbour.

‘Andalusian is not Spanish,’ he said, ‘you have much work to do here before you can carry on a conversation.’

And so it proved.

We were reminded of that day as we tried to speak with the man following along behind his horses. Even the tried and trusted truncations of the ‘me Tarzan, you Jane’ variety proved useless. Whatever variation of Spanish he was speaking was far beyond our comprehension.

Persevering, I learnt the two horses were ‘amigos’ and had been together as a pair for twenty years and that his father had ‘retired’ from ploughing two years ago. At the age of 88! He pointed out his father, several fields away, snipping away at the vines on a steep hillside. Presumably, this pruning work being the ‘light duties’ he now performed after all those years of ploughing.

‘I don’t even think I could get up to where he is working,’ Marigold said.

‘Me neither.’

We waved goodbye after asking if we could take a photo of him and his horses. He was happy to do so and we left with our respect for these Stakhanovite sons of the soil raised even higher in our estimation.

There’s ‘dad’ on light duty vine pruning. Aged 88.

A few miles further on we saw two very old men shaking olive trees and collecting their bounty in a net. No fancy machinery, just a couple of octogenarians doing what they’ve done all their lives. Will the next generation be performing back breaking labour into old age as subsistence farmers as their fathers did and their fathers before them? We already feel we know the answer to that question. This may be the end of a way of life that’s survived over many hundreds of years.

We’re sad to see the old ways die off, but opportunities in education and travel have revealed other ways of earning a living. I wonder aloud whether I’d ever contemplate spending my extreme old age scrabbling around on a steep hillside with just a pair of secateurs for company. Marigold doesn’t say anything, but gives me one of her ‘looks.’

There are cork trees, chestnut trees, olive and almond trees and a riotous display of blossom lining the roads and always, always the views of the surrounding hills are magnificent.

Eagles, eh? Give up trying to take a photo and they turn up anyway. Photobombing, eagle style.

On the road to Bubin we watch a pair of eagles swooping and soaring, their keen eyes no doubt watching the valley floor far below. As we’re so high, they’re practically at our eye level. I try, without success, to capture them on film, but they’re so fast and change direction so unpredictably I give up. Later, I see they’ve both appeared in shot in another photo I took of the hillside views opposite and I hadn’t even noticed them at the time.

As we prepare to drive on another pair of eagles appear, much higher in the sky. Not a good day to be a rabbit in this valley.

We’ve seen many walkers setting off for a day in the hills, festooned in many layers of clothes and sturdy boots. Most of the visitors we’ve seen are here for the walking, but it’s an area renowned for bird watching too and we see a pair seemingly equipped for a trip to Antarctica getting very excited about a pair of hoopoes, of which we’ve seen dozens on this trip, completely oblivious to the four eagles soaring overhead.

Bubion is only about a mile from Capileira and it’s the village we’re most familiar with in this area as we stayed here for a couple of nights about ten years ago. Needless to say, we can’t find the house we stayed in even though so much else is familiar. A few walkers are setting off in little groups, wearing odd knitted hats, big clumpy boots and (perceived) expressions of superiority. They’ve all got sticks and weatherbeaten faces too. I’ve nothing against walking, we certainly do plenty of it, but there’s a certain ‘type’ of walker where being in a group appears to give off vibes of superiority, especially towards those who are sitting in a car.

‘Look at us’ I suspect they are thinking, ‘see how fit we are, how smug and comfortable in our presumption of longevity.’

Marigold points out the three at the back, two men with very red faces and a woman who looks as if she’d rather be sitting by the fire, eating biscuits yet are probably the most expensively equipped of the whole group, are puffing a fair bit and they’ve only walked a few hundred yards and are still on a firm, even surface. That’s another thing that annoys me: the competitive nature of the ‘leaders,’ making a point to the less accomplished members at the rear. As with cyclists where one, almost always the man, rides half a mile in front of his female partner, particularly on the hills, what’s the point? If I walk or cycle with Marigold, we stay together, we talk, we share the experience. Why can’t this ‘group’ stay together as a group? They’ve already fragmented and they’ve only been walking for ten minutes, at most. Walking ‘group,’ do me a favour.

‘You’re ranting, again,’ Marigold says as I grumble away. Yes, I know I am, but I have no problem with ‘walkers’ at all; wonderful exercise in the open air in the company of others, but I do wish it didn’t so often denigrate into a competitive display of showing off.

A social group, walking together as a united group, in the countryside, sharing the experience, I’d happily join that group. As would Marigold, although if there were too many hills she’d resent getting out of breath as it may mean talking would become difficult.

We don’t go down as far as the church (not because it’s too far to walk, but because I’m still hoping to stay in touch with the eagles) but move on instead, not very far, to another pretty village, neighbouring Pampaneira.

Pampaneira has hams, of course it does, but is also renowned for its chocolate.

It’s only a small village with narrow streets, but amongst these narrow alleys is Abuela Ili (Grandma Ili) which specialises in artisan chocolate. We bustle along, still very much aware of how ‘nippy’ it is out of the sun, only to find Grandma’s shop is closed. Cue much weeping, wailing and gnashing of teeth.

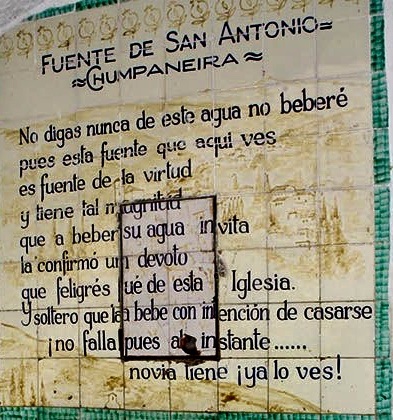

We console ourselves, well not really, by visiting the Fuente de San Antonio, (Saint Anthony’s Fountain), known locally as Chumpaneira, very popular amongst ‘unattached’ young men. The closest I can get to a translation of the inscription it bears is ‘it has such a magnitude that, a bachelor who drinks with the intention of marrying does not fail, because he has a girlfriend at once. You’ll see!’

Marigold points out a couple of local men sitting on a wall nearby. They’re tucking into a stercoraceous concoction with evident relish, presumably a shared breakfast on a paper plate placed between them. Like their meal the pair are quite spectacularly unattractive in appearance and their chances of finding a girlfriend are surely pretty remote, Marigold suggests.

She wonders if she should take a glass of water from the fountain over to them as it may improve their prospects. On second thoughts, she decides such an approach could be misconstrued and leaves them to their bachelor state. Even worse, they may ask her to share their meal.

We know what to expect when we get to Trevlez: hams and cold air. Trevlez is 1,476 metres – that’s just over 4,840 feet – above sea level, making it the highest permanent settlement in Spain, but this altitude makes it a pretty nippy place in February. The last time we were here was in summer and it was certainly not a teeshirt day on that occasion either.

Hams are the first thing we see on entering the village, a fancy sort of delicatessen with numerous hanging hams. If the mountain air of the Alpujarras is ideal for drying hams, then Trevlez is ham drying perfection. The village is divided into three barrios: bajo, medio and alto. The lower section, Barrio Bajo, is the most tourist friendly out of the three with handicraft shops, bars and restaurants. We wander up to a restaurant with an inviting lunchtime menu, but inside is bedlam ‘ the young lad behind the bar seems happy enough to have his rap music blaring out at distortion level, but nobody else is there to share the experience – while the plastic seats outside in the cold are hardly inviting.

There’s a ham museum, complete with a giant ham outside, further up the hill, but it’s closed. Of course it is. Back down in the square, we meet up with a couple of walkers, Brits, who are topping up their water bottles from one of the fountains.

‘It’s freezing,’ the man says to us, sipping from his bottle. He’s drinking what is almost certainly melted snow off the mountain, but still seems surprised. They tell us they got up at dawn and have walked all the way up from the valley. Impressive, but given the man is a) in his 60s, b) at least three stone overweight and c) has both knees heavily strapped perhaps a little foolhardy as well. His wife, Muriel, is small, very thin and looks as if a strong gust of wind would blow her over.

Marigold rolls her eyes as this brief exchange seems likely to develop into a lengthy exchange. The man seems intent on bloviating away, talking at us rather than to us, purely because we share a common language.

They may be perfectly nice people, but seem intent on chatting away for hours and I’m well aware Marigold would far rather be indoors out of the cold with food and drink in front of her.

The man, I’ve forgotten his name or deliberately blotted it from my memory, and Muriel stop talking for a moment while he tries to open a very narrow door on the assumption it is the entrance to a public toilet. Which it isn’t.

I point out to him that it doesn’t have a handle with which to open it, just a decorative knob. I don’t say, ‘you’d never get your belly through that door anyway,’ but I want to. He’s getting a bit cross, banging on the door and getting very red in the face. I notice he has eyes of different colours and whisper ‘heterochromia’ to Marigold at the exact same instant she whispers ‘David Bowie’ to me.

‘I see your David Bowie and raise you Benedict Cumberbatch,’ I hiss, relishing Marigold’s annoyance at not being able to think of another with this condition.

Hours later Marigold shouts out ‘Kiefer Sutherland’ and I look at her doubtfully, but if course when I check her ‘facts’ the next day, she is right. Kiefer Sutherland does indeed possess eyes of different colours.

By now Beryl has got her husband under control. ‘We’ve decided to walk to the summit of Mount Mulhacen,’ she announces, waving a bony talon up at the snow capped mountain high above the village. ‘Where does one find a map of the best routes?’

There is indeed a walk to the summit, starting from this village, and we know people who have done it. But, the round trip is a two day expedition not just a hike, it’s only recommended in ideal walking conditions, basically meaning in the summer months when the snow has melted, and the people we know who have done this climb all look a lot fitter than this pair of crocks. Who would carry that man back down the mountain if he twists an ankle? Certainly not Muriel.

‘There’s a tourist office over there with all the info,’ Marigold says, brightly, and they toddle off. He’s already limping and this is a paved village square, not a mountain.

I look quizzically at Marigold. ‘Well, there might be a tourist office over there,’ she says. ‘Why don’t we go and find a cafe?’

So we do.

An eight year old child may have been able to fit through this door. Not an 18 stone man.

It’s not easy to find food here that doesn’t feature ham. I choose habas con jamn, which is simply broad beans and ham and Marigold picks an item off the menu about which neither of us have a clue as to what it is (she does this quite often) and when it arrives we still have no idea what’s in it. Apart from chunks of ham, obviously. It tastes good though and we munch our way through another couple of dishes happily enough. The local speciality is Plato Alpujarreno containing potatoes, peppers, egg and black pudding with very thinly sliced ham is delicious, and I’m not normally all that fond of black pudding.

This is rustic food, peasant food, of a kind these villagers have been eating for generations, but it hits the spot. We’ve enjoyed our few days up in the mountains very much. Would we come here again, in February?

Of course not.

‘Change of scenery?’ I say.

‘Will it be warmer?’

‘Much.’

Marigold throws her top layer onto the back seat and gets into the car.

‘Drive,’ she says.

Valentines Day should involve warmth, in all respects, so we’re back on the coast soon enough and the difference in temperature is staggering. One or two degrees in the mountains, here it’s a tee shirt and shorts day. Not that I have shorts with me, but we remove layers as far as decency permits – must think of others – and we set off with a specific place in mind.

Roquetas del Mar is by the sea – there’s a bit of a clue in the name – but it’s mostly shops, plastic greenhouses and fruit and veg packing depots as far as the eye can see. We press on as there’s a wonderful beach area here for those with enough perseverance to find it. We’ve been before, so we know it’s here, but there’s a lot of Roquetas del Mar to get through on the way.

We’re late for lunch, Valentines Day or not, but meal times in Spain are a movable feast, literally, and everywhere along the promenade is open. There’s one beachfront restaurant advertising a Valentines Day lunch for 47.50 euros. It’s empty and judging by the waiters’ bored expressions has been empty all day.

We jump into the only spare seats at the place next door which is packed.

We’ve been here before and the waiter recognises us, always nice, and serves up a couple of tapas even before we order a drink which is even nicer.

We munch away and decide to stick with tapas. 1.50 euros each and big portions. We order another four (no, not four each) and share a lovely meal in the sunshine looking out at a blue sea and a cloudless sky.

Perfect Valentines Day lunch? Well, we think so, but we’re in a minority on this terrace. Every other group of diners here is having a ‘domestic.’ The Germans next to us – three couples – are all dressed up and have ordered huge amounts of food and several bottles of wine between them. They’re at each others’ throats – I blame the wine – with the respective couples only stopping their arguments to temporarily join forces in an attack on their ‘friends.’

Of course, we’re loving it. Our waiter comes to our table, winks at us and says ‘everybody happy here?’ We laugh with him and he dashes off as further along the terrace a chair is over turned and a fresh commotion breaks out.

‘Aren’t we a boring pair?’ Marigold whispers. No need to whisper really, it’s bedlam here. Even the ‘lookie-lookie men are turning back and avoiding the area.

It all settles down, eventually. The Germans next to us start singing, badly but very loudly, arm in arm, their differences now apparently forgotten and we decide we need to leave. Riotous alcohol fuelled argument is fine as a spectator sport, but alcohol fuelled singing is quite a different matter.

‘Time to go, Zebedee,’ says Marigold.

The only pitched roof we found, everything else had a flat roof.

This could easily have been a mountain village house in North Africa

Access to these houses, especially the isolated ones, isn’t easy, the main road ended many miles back

I briefly considered going to stand on the top of that left hand rock. It was very windy and Marigold was worried in case I fell off and she would have to replace the phone. I used this photograph as the cover of a novel I wrote set in Andalusia